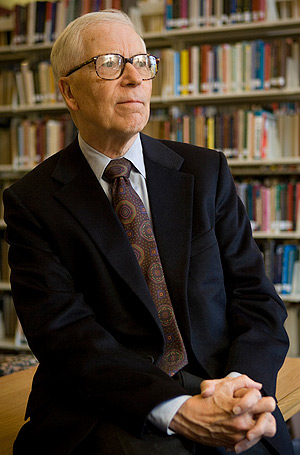

2004: Retiring: Jim Barefield

The inimitable Dr. B

By Rogan Kersh (’86)

From Wake Forest Magazine

I knew Jim Barefield only slightly — as “Dr. B,” which his legions of devoted students invariably called him — when he greeted me outside Tribble Hall one rainy Sunday afternoon. “I’m taking a group to Venice next year,” he said in that inimitably raspy voice. “I think you might enjoy it.” As a sophomore, I hadn’t thought much about an overseas semester, but something in Dr. B’s manner inspired confidence. “Sure,” I said. “I’d love to go.”

On that as so many other occasions, I took my cue from one of the most remarkable figures in Wake Forest’s modern history. Jim Barefield arrived in Winston-Salem in 1963, ambled into his first class in 102A Tribble Hall, and began a teaching career that epitomizes the term. True teachers — those who touch students’ lives in deeply meaningful ways both in and beyond the classroom — are as rare as they are cherished; countless former Barefield students know him as a prime example.

The South has been Barefield’s home all his life, an important (though by no means the sole) defining feature of his character. Barefield was born in Jacksonville, Florida, moved to Atlanta at eleven, and finished high school in Birmingham — a school of unusual distinction; his twelve-member senior U.S. history class featured an assortment of future academics, public servants, and captains of industry. After attending Rice University Barefield completed his Ph.D. at Johns Hopkins, along the way winning a Fulbright fellowship to study in London, where his lifelong passion for European history was cemented. As was his particular devotion to the musical “Oliver!,” which he once confessed to having seen some two dozen times during his stay.

Retiring this spring as Wake Forest Professor of History, Barefield has been instrumental in three vital areas: honors, overseas programs, and merit scholarships. He is an architect of the University’s pathbreaking honors program, pioneering its signature “Three Figures” courses and teaching many memorable editions of these, as well as creating the cornerstone honors classes “The Ironic View” and “The Comic View.” (During his years heading the program, his well-known aversion to committees was on display; though there was a formal Honors Committee, chairman Barefield somehow never got around to convening a single meeting.)

Students fortunate enough to have traveled with him to Venice’s Casa Artom, or the Worrell House in London, well remember the magical semesters he supervised there. He also did much to build these and Wake Forest’s other overseas offerings into the nationally prominent network that students enjoy today. And a generation of Reynolds, Carswell, and other scholarship holders owe more than they know to his service to the University’s merit programs. Equally important, Barefield has worked extensively with virtually all Wake Forest seniors competing for prestigious postgraduate scholarships like the Rhodes, Marshall, Fulbright, and Luce. The University’s stunning success in this area (eight Rhodes winners in the past eighteen years, for example) owes more to Jim Barefield than to anyone else on campus.

With all this, Barefield’s greatest contributions are in the classroom. Wake Forest’s faculty has long included an uncommonly high proportion of engaging, committed lecturers and seminar leaders. Barefield is prominent among this group (students still show up early for lecture to witness his patented teabag routine), but his courses are unforgettable for other reasons as well. For one, his reading lists are legendary, featuring an eclectic array of books chosen not because they fit into some ideology or canon, but because Barefield loved them, and thought we ought to as well.

Long after most of my college texts have been packed away, I still have nearby — and read and reread — many of those “Barefield books”: di Lampedusa’s great allegorical novel, The Leopard; Henry Adams’ insightful meditations on American history, only now returning into vogue among U.S. historians; Northrop Frye’s demanding but rewarding Anatomy of Criticism. Reading these inspiring books under his gentle influence, we were in turn inspired. Nearly twenty years later I can recall intense discussions with my classmates, spilling outside the confines of the seminar room, about Hans Castorp’s actions in The Magic Mountain or the uncertain nature of historical memory.

Barefield’s influence is felt far beyond even this extraordinary intellectual guidance. In ways so subtle that many of us are only now recognizing them, Dr. B helped us with the arduous work of charting the course of our lives. I’m among dozens of former students who visit or call him regularly, usually just to catch up but also whenever we reach a personal crossroads. (And for even greater purposes: when Barefield lived in Reynolda Village, he hosted in his side yard at least one wedding of a former student.) If imitation remains the highest form of homage, it is surely no coincidence that so many of Barefield’s students wind up in the academy as well—striving to realize something of his example in our own classes.

Barefield is also a true scholar, in an “old-school” sense. Newly minted professors today, facing the pressures of the tenure clock, often rush ideas into print before they are fully formed. In a more traditional style of inquiry, Barefield is now distilling four decades of teaching and reflection into a study of irony in historical writing; his book quite simply will be the authoritative work on that complex and important subject.

As well as Barefield’s field of greatest expertise, irony is his habitual outlook. Anyone who has seen his eyebrow arched quizzically in class needs no further introduction to the ironic view. But there is nothing ironic in his abiding interest in and concern for his students, continuing long after they leave campus. Nor is there a hint of irony in the profound respect, gratitude, and — yes — love that so many of us will always feel in return. If the enduring legacy of Wake Forest is the lessons its students carry into the world, then the University remains profoundly fortunate to have had Jim Barefield to instill them.

Rogan Kersh (’86) was a Reynolds Scholar at Wake Forest and is professor of political science at the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs, Syracuse University. He eagerly anticipates any care packages from Stamey’s Barbecue.