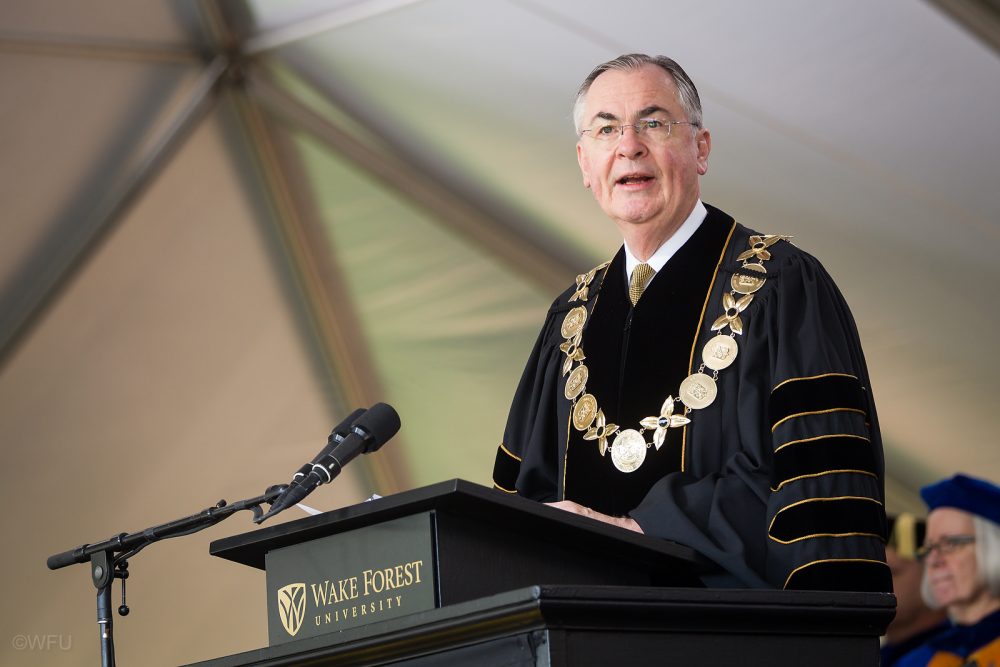

2014: President Hatch

Swing

Wake Forest Commencement Service

By Nathan O. Hatch

May 19, 2014

I recently read an inspiring book by Daniel James Brown, “Boys in the Boat.” He tells the improbable story of how, in 1936, the eight-oar men’s crew team from the University of Washington came from nowhere to become the very best rowing team in the world. They began their quest by besting their rivals from the west coast, The University of California, Berkeley, and then went on to humble the long-established elite of rowing from the Ivy League.

Against all odds, these lads from the Northwest became the United States Olympic team; and, in Berlin, they took on the best from Oxford and Cambridge, from Italy and Germany. In front of Adolf Hitler himself and a crowd of 75,000 spectators screaming “Deutschland, Deutschland,” these young Americans, and their shell, the Husky Clipper, came from behind to win the gold medal.

This crew team was comprised of upstarts, nine working-class lads from dusty small towns in the Northwest, from logging camps, shipyards, and dairy farms. Most of them had known the ravages of the depression. One of them, Joe Rantz had actually been abandoned by his family at age 16 when they determined there were too many mouths to feed. It is an epic saga; someone has said a kind of Chariots of Fire with oars.

It is a story of tremendous determination, of backbreaking hard work and of masterful and innovative coaching. But most of all, it is a story of tremendous teamwork — and that is my theme today.

I drew my title from what crew teams call “swing.” Swing is a kind of “fourth dimension of rowing” — hard to achieve and hard to define. “Many crews, even winning crews never really find it. … It only happens when all eight oarsmen are rowing in such perfect unison that no single action by any one is out of synch with those of all the others. … Sixteen arms must begin to pull, sixteen knees must begin to fold and unfold, eight bodies must begin to slide forward and backward, and eight backs must bend and straighten all at once. Only then will the boat continue to run, unchecked, fluidly and gracefully between pulls of the oar. Only then will it feels as if the boat is part of each of them, moving as if on its own. Only then does pain entirely give way to exultation.”

Today I want to extoll the joys and the possibilities of teamwork. I have only watched rowing at a distance, but I have experienced a different kind of swing, the deep fulfillment of a team really coming together to accomplish important things, where the whole does become greater than the sum of the parts.

As a young historian, I fell in with a remarkable set of colleagues working in similar fields. We took on projects together and met in the summer —with our families — to read and criticize each other’s work. This scholarly community produced numerous conferences, published a set of articles and books, and mentored a number of young historians — an impact we never could have had working by ourselves.

Some of you graduating today may have already experienced the power of a team: in working on “Hit the Bricks” or “Wake and Shake,” in collaborating with a set of friends to build a student organization, in going all out in a club sport, or in finding a study group or laboratory team that really clicked.

On occasions like today, most advice is directed at you graduates as individuals. You are counseled to follow your passion, march to the beat of your own drummer, follow your dreams. This advice is certainly useful. But today I want to hold up a complimentary ideal: that as you pursue your own dream, you also look for those occasions to find, join or to build a team.

Finding a team with “swing” is rare and elusive. Yet it is an ideal worth pursuing, an aspiration worth working towards. The right kind of team can achieve things unimaginable for you as an individual.

Let me say four things about successful teams.

First, innovation is increasingly a group endeavor. A recent study shows that teamwork is a defining trend of modern scientific research. The most cited studies in a field used to be the product of lone geniuses, but no longer. Given the complexity of modern problems, from medicine to law, from politics to business, it is teams that will make real breakthroughs.[1]

Second, teams are difficult to build and sustain. Strong personalities have to come together and be willing to give up some of their cherished autonomy—and everyone doesn’t want to do this. Teams don’t just happen. They demand careful listening, constant adjustment, and resolving conflict. They demand time and more time. And the right kind of working spaces. Shared places seem to have played an outsized role in the history of creative teams from 18th century coffeehouses in London to twentieth-century garages in Silicon Valley. The best advice I can give is to put yourself in the right kind of place and think more about what you can learn from others than how you can display our own insights.

Third, teams are more about attitude and outlook than sheer talent. George Pocock, a major figure in developing the Washington rowing team in 1936, had come to Seattle from England as a craftsman of exquisite racing shells. The shell that he built for the Olympics, the Husky Clipper, is hung with honor today in the University of Washington boathouse.

Pocock was also a great judge of character and motivation. He understood that, success had as much to do with spirit, will, and mutual trust as it did sheer brawn. What was extraordinary about “the boys in the boat” was not their physical prowess, but their melding as a unit committed to each other and to accomplishing extraordinary goals. He called it rowing with head and heart.

This is something the Washington crew team had to learn. Joe Rantz, the real hero of the book, was defiantly independent of necessity, having raised himself and having to work two or three jobs to pay his college bills. Joe had talent, but was defiantly independent and thus erratic in the boat. At one point George Pocock took him aside and told him, Joe, you row as if he were the only person in the boat. You attack the water as if the race were all up to you. Pocock knew that it was not how hard he rowed but how well he harmonized with others. “And a man can’t harmonize with his crewmates,” he advised, “unless you open your heart to them.”

He knew that great teams require trust in each other. In a recent interview, Laszlo Bock, the Google executive in charge of hiring, took note the kinds of young people that Google is looking for: those who meld into effective teams. “You need a big ego and a small ego in the same person at the same time.” They are seeking young people who have strong and creative ideas, but are also willing to defer to someone with a better idea. In short, teams require a degree of intellectual humility, putting the larger good ahead of who gets the credit.

A fourth mark of great teams is that they are diverse and see conflict as essential. Steve Jobs was a great believer in teams, but he feared the danger of “group-think,” an attitude of “don’t confront me and I won’t confront you.”

In describing a healthy team, Jobs told a story from his boyhood about a neighbor who invited him to put some common rocks into a rock tumbler. The next day Jobs came back and found amazingly beautiful polished stones. That became his metaphor for a team: “talented people bumping up against each other, having arguments, having fights sometimes, making noise, and working together they polish each other and they polish the ideas and what comes out are those beautiful stones.”

Today, I have suggested four things about teams: that they are seedbeds of innovation, that they are difficult to nurture, that they are based on attitude and commitment, not just talent, and they work best when they blend commitment and diversity.

There is one last reason to work towards being part of a great team. It can be a sheer personal delight. George Pocock wrote about the exhilaration that rowing teams found when they achieved the perfect harmony of “swing.” He said, “I’ve heard men shriek out with delight when that swing came in … “It’s a thing they’ll never forget as long as they live.”

There’s nothing like being in a great team. It can turn the rigors of work into a delight. To bond with others, in pursuit of accomplishing great things, is a rare privilege and a worthy prize. May all of you, at one time or another, come to know that level of commitment and that exhilaration which “the boys in the boat” called “swing.”

[1] Wuchty, Stefan, Benjamin F Jones and Brian Uzzi. 2007. The Increasing Dominance of Teams in the Production of Knowledge. Science. 316(5827): 1036-1039.

- 2014: Main story

- 2014: Speaker Jill Abramson

- 2014: President Hatch

- 2014: Commencement Photos

- 2014: Commencement Videos

- 2014: Honorary degrees

- 2014: Senior Profiles

- 2014: Meaningful Mentoring

- 2014: Baccalaureate Speaker Melissa Rogers

- 2014: Baccalaureate Photos

- 2014: Baccalaureate Video

- 2014: Baccalaureate Timelapse

- 2014: Retirees

- 2014: By the Numbers

- 2014: Programs