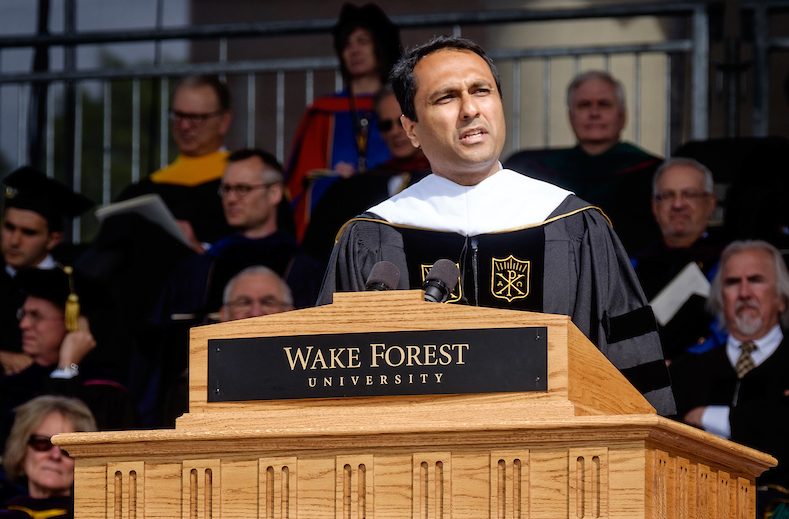

2016: Speaker Eboo Patel

The Jazz Age

A Message to the Wake Forest Graduating Class of 2016

In the early part of the twentieth century, a group of esteemed scholars gathered in Boston to take up an urgent question: Would the United States ever make a unique contribution to music? Could there be, out there somewhere, an American Bach?

They looked far and wide in the places that they knew, they searched for faces that they might recognize, they listened deeply in the idioms in which they were familiar. And they came away disappointed.

The jazz critic Gary Giddins shakes his head as he recounts the tale. If these so-called experts had simply taken a train south from Boston to New York City and stepped in to the Roseland Ballroom on a Thursday night, they would have experienced the American Bach, Dante and Shakespeare all rolled in to one. Louie Armstrong.

Born to a sixteen year old girl who sometimes worked as a prostitute, raised in a New Orleans neighborhood so violent it was known as the Battlefield, sent to a juvenile detention facility at eleven for firing a gun into the street – let’s just say that this was not the profile that the aforementioned experts had in mind.

And yet, Louie Armstrong virtually invented American music. Duke Ellington said Louie Armstrong was so good he wanted him on every instrument. Wynton Marsalis commented that the only way to describe his sound was to say there was light in it. Ken Burns wrote that Louie Armstrong is to American music what Einstein is to physics, Freud is to medicine and the Wright Brothers are to travel. As for himself, Armstrong liked to say that his purpose was to blow his horn so beautifully Angel Gabriel would come out of the clouds.

I love the image of the black, working-class patrons of nightclubs in Harlem and Bronzeville swinging to the genius of Louie Armstrong while the academic elite wrung their hands in stuffy boardrooms wondering whether such a figure existed. Reminds me that there’s more than one definition of being educated. And if I’m honest with myself, reminds me that my pedigree is more likely to place me in a stuffy boardroom wringing my hands than in a Harlem nightclub swinging to the next American genius.

And as of today, yours does too.

And so allow me to speak to you about the burden that is customarily placed on the education you received at this fine institution. The burden of certainty. Of knowing. Of believing that you leave here with a set definition of what treasure or genius or success looks like, and a clear road map for how to find it. It’s a view that understands an elite education as a classical music score. You’ve done the hard work of putting the notes on the page, now all you have to do is play them – go to the right grad program, get the right first job, and presto, the music of the good life.

Who can blame anyone for wanting this? The world feels so insecure. If you work this hard and pay this much, the least you can expect is certainty, right?

Well, I have good news and bad news. The bad news is that the world is even more insecure than you’ve been led to believe. You may end up not liking the sound of the symphony that you spent your education putting on the page. And anything you can write down and follow, a machine is likely to be able to play better, or faster, or at least cheaper.

All of this makes your Wake Forest education even more valuable. (This, by the way, is the good news.) There are things machines can’t do, only humans can. These include telling stories, offering comfort, building teams, framing problems, inspiring others. The people most ready to do these very human things are the ones who carry liberal arts thinking deep in their bones. People who have a healthy suspicion of sameness and a knack for finding ideas on the margins and integrating them into the center. People who can take things apart and put them together again, on the fly, in ensemble. In other words, people who have absorbed the music so fully, they can improvise.

Wynton Marsallis says that he plays both classical music and jazz, and jazz is much harder. Not only do you have to know the notes and instrument cold, you have to listen to what other people are doing, and create as you go along.

Louie Armstrong was a master. When his sheet music fell off the stand in a recording session, he didn’t stop the tape, he just sang a string of rhythmic nonsense, inventing on the spot a whole new dimension to jazz music: scat.

There are a lot of missteps when you’re improvising. You try this, it doesn’t sound so good. You try that, it comes out worse. There’s no shame in those kind of mistakes. Having a failed company or two is a badge of honor in Silicon Valley. The only shame is in stagnation, or not doing the work.

Ask anybody you admire about what they hoped would happen in their lives that didn’t, and you get a glimpse into the most interesting part of their story. When I was in high school, I was hell-bent on playing Varsity Basketball. I worked and worked and worked – left hand layups, mid-range jumpers. I was devastated when I didn’t make the cut. But I had to find something to do with my time, so I joined speech team. Let’s just say that my basketball prowess was unlikely to get me to Wake Forest.

I’m not telling you to throw away the road map you’ve sketched for your life. I’m just saying that your liberal arts education has given you the eyes to read the road signs along the way, and the ability to change direction when the original plan goes sideways. There is something to be said for reaching the milestones you set for yourself. There’s a lot more involved in re-charting your course when you miss them.

This isn’t just how careers are made, it’s also how countries are built. You are at a jazz age in your lives and we are at a new jazz age as a nation. Wynton Marsalis says that “The foundation of both jazz and democracy is dialogue, learning to negotiate your own agenda within the group’s agenda … You have to listen to what others have to say if you’re going to make an intelligent contribution.”

In doing this, we have to pay special attention to those who are different, unfamiliar, strange. As Marsalis puts it, to “invest energy in people who are not like us … invest in them to keep the whole system working.”

Remember those highly-educated experts I mentioned at the beginning – the ones so focused on finding the American Bach that they missed Louie Armstrong? Well, there was another set of people who displayed a wider sense of wonder. The Karnofskys, a Jewish family from Russia, owned a junk wagon and hired young Louie Armstrong to blow the tin horn when the wagon entered a new neighborhood. They took Louie into their home, made sure he had a good meal at the end of every night, invited him to join in the singing of Jewish lullabies around their dinner table.

Something about that tin horn, those Russian Jewish melodies, that extra bit of love, turned something in young Louie Armstrong. When he saw a cornet in a corner store, he asked the Karnofskys for a $5 advance to buy it. He put the instrument to his lips, and lo and behold, songs came out. The early notes of American music.

Louie Armstrong wore a Star of David until he died out of gratitude for the role the Karnofsky’s played in his life.

Think about that. A Russian Jewish family who owned a junk wagon nurtured the musical genius of a black teenage prostitute’s son from a New Orleans ghetto.

That’s not just the history of the American songbook. That’s the essence of the American story.