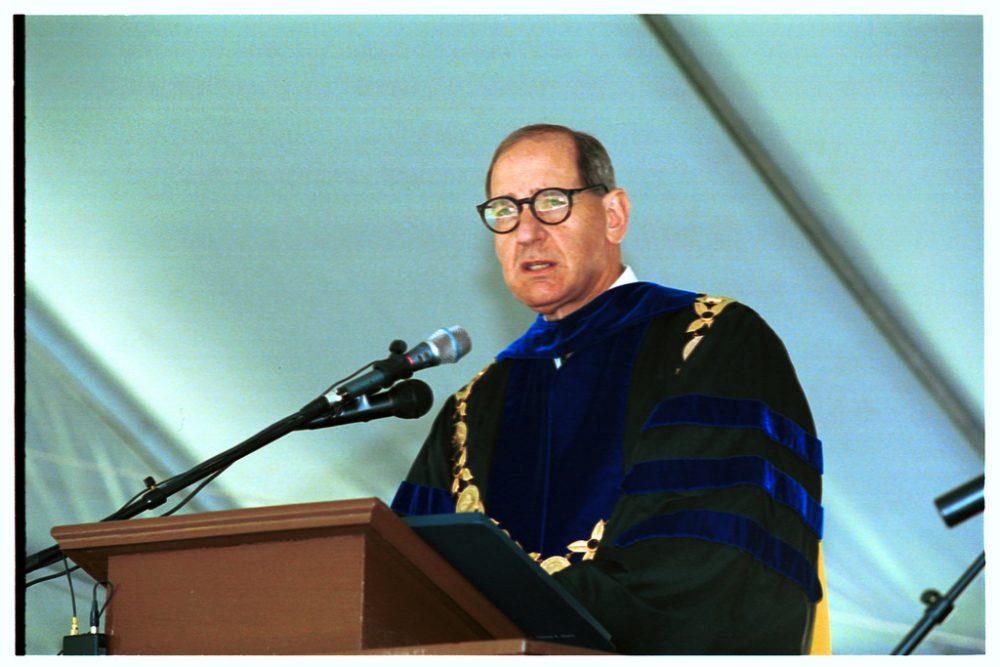

2000: President Hearn

Truth with a capital “T”

Charge to Graduates

By President Thomas K. Hearn Jr.

May 15, 2000

I know precisely when my education – as opposed to my schooling – began. I was a college sophomore taking my first courses in philosophy and anthropology. In philosophy we were studying the great Socratic dialogues, with special attention to those epochal disputes between Socrates and a group of teachers called Sophists (who gave “sophistry” its ill name).

Their quarrels centered on whether there could be knowledge and truth, as Socrates held, or, as the sophist Protagoras said, “Man is the measure of all things.” As things appear to each person, so they are. Sophists taught that since there are no truthful answers to questions, disputes were based on rhetorical skill, not the facts of the matter.

Meanwhile, in anthropology, I was reading Ruth Benedict, Margaret Mead, and William Graham Sumner, being introduced to the idea of cultural relativism, the notion that our beliefs and values are products of culture and change over time and place. Truth is culturally and historically conditioned.

At some point, I realized that these two courses were about the same topic-philosophy, with thinkers from the 5th Century B.C., and anthropology, with writers of the mid-20th Century. What was at issue was the possibility of capital “T” Truth. Now, there was a subject to fire a sophomore’s imagination.

I found myself wanting to understand these topics, not for my courses or for a grade, but because I wanted to know for its own sake. I was hooked on learning, hooked on philosophy. It was exhilarating. I was on my way to the academy as my place of service.

I concluded that Socrates was right. The Sophists and the Cultural Relativists were wrong. Truth is possible – difficult and elusive – but possible. It certainly made no sense, I cleverly reasoned, to argue as a matter of truth-as Protagoras did-that truth is unattainable.

My sophomore’s faith in truth has faced severe challenge in the long years since. My observation of the disciplines within the academy, as well as the posture of the larger cultural climate, is the sophists have prevailed. Relativism is the order of these days.

This triumph of the Sophists has always been surprising and paradoxical to me. For relativism contradicts what the last half-century has apparently established in our experience. Let me explain.

No developments of recent history have been of greater intellectual and cultural significance than the dramatic advances in science. Time magazine’s Person of the Century was Albert Einstein, not only for his singular contributions, but also in recognition of scientific advancement across a broad array of intellectual frontiers. This session, Wake Forest celebrated The Year of Science and Technology as a tribute to these accomplishments.

These intellectual developments would seem to lead naturally and inevitably to the reinforcement of the rationalist’s faith in the mind’s progressive grasp of truth. The entire premise of the modern era is that knowledge gives us power to create technologies that improve and extend life.

However, outside of the sciences-and sometimes even within the sciences-there is widespread skepticism in academic disciplines about the possibility of even scientific knowledge. Post-modernism and post-enlightenment are terms used to characterize our age. The apostles of this new perspective concur that knowing is culturally and psychologically determined. We cannot know what is, only what appears to be. There is no truth, there is only received opinion.

The reasons for this skeptical climate are culturally complex. But skepticism is in no wise what one would expect in a world in which the genetic code is being blueprinted, the internet age is unfolding, and, indeed, the deepest mysteries of cosmology are yielding to our understanding.

In the history of our moral consciousness, there is a similar disconnection between our historical experience and the theoretical posture of our age. In recent moral history, no event stands out like the Holocaust. The lessons of this tragedy-too-great-for-speaking repudiate moral relativism. The relativist says that good and right are culturally determined. But, it did not matter morally that the Nazi Government was legitimate or whether this terror was the result of generally accepted anti-Semitic social norms. Observations of social mores are irrelevant to the moral assessment of what happened. The Holocaust taught us, vividly, and I would have thought forever, that human beings possess rights not bestowed by governments or dependent upon social mores.

Yet that morally certain lesson failed in its effect on the academy and in the larger society. We read in textbooks of discipline after discipline that morals and values are relative to time, place, and circumstance. It has become a virtual truism that democracy and tolerance require that equal consideration be given to every moral position.

Thus, the moral universalism that the world seemed to learn from the Holocaust stands in stark contrast with a presumed moral democracy in which every view is entitled to equal regard. And, yes, I participated once in a Wake Forest class in which the students were reluctant to denounce Hitler as a monster. He was, as one student said, a man of his own time. We cannot judge him by our different standards.

So I had thought this battle-begun for me as a sophomore-for truth and right had been lost. But my pessimism was ill-founded. A remarkable event at Wake Forest this spring has restored my faith in reason and in the lessons of my sophomore’s quest. The issue of Holocaust Revisionism arrived here like a maelstrom. The controversy consumed our collective awareness.

And this rationalist learned a reassuring fact about Wake Forest and, I suspect, a fact about human beings in general. I like being able to say this: in the face of lived experience, no one is a relativist. Our campus rose up to demand that truth be honored, and that the horrific crimes of the Holocaust be called by the infamous names that they deserve.

In one of my first meetings of the crisis, someone said, “Truth is the issue here. Wake Forest must stand for the truth.” From the emphatic way she said the word, I knew that she meant capital T “Truth”. I had an almost irresistible urge to hug her.

No campus voice rose to say, as skeptical historical theorists have it, “that since all history-writing is a subjective representation; all pasts constructed, it makes no sense to seek a consensus about what really happened in history. There is no objective truth. I have my goals and values, you have yours, and we choose our past accordingly.”

Were we to believe this skeptical view, we would, of course, have to allow the Revisionists their construct. Only truth can refute error. Absent an established truth of the matter, the claims of Revisionism cannot be judged false or even labeled as propaganda.

Truth, with a capital “T”, was the campus outcry. While I regretted the controversy, I was reassured by our common response. I trust we learned this lesson not for this day only, but also for other days. A university exists for the discovery of the truth. The quest for truth is the foundation of our academic mission.

And there is also moral truth. Our anger and anguish pointed to the unspeakable wrongs of the Holocaust – wrongs for which no words of condemnation are adequate. Our campus had an encounter with a central moral truth: that God-given human rights are not the province of governments and societies to bestow or withhold. May our commitment to this truth never be lost or forgotten.

You see, the basis for tolerance is not relativism. The reason we must tolerate and, more than that, act in positive goodwill toward our fellow human beings is that all of us are possessed of these inalienable rights.

The diploma you are about to receive charges you, as a consequence of the education given, to live in service of the ideal of Pro Humanitate. It is the same ideal of truth and goodness that I am advocating. The quest for truth must be your guide in all things. Among the truths to live by is that humanity, here and now, everywhere and for all time, must be the recipient of our active goodwill. We must extend these God-given rights to our brothers and sisters of all tribes and nations.

The task of your generation is to construct a world culture. You must create a world made safe for human and creature habitation, a world where our differences are resolved through negotiation based on mutual respect, a world where the needs of those least among us are met by the effort of all. Such is the vision of the future embodied in the aspiration of Pro Humanitate. Go forth, and in your varied spheres of service, bring that world to pass.