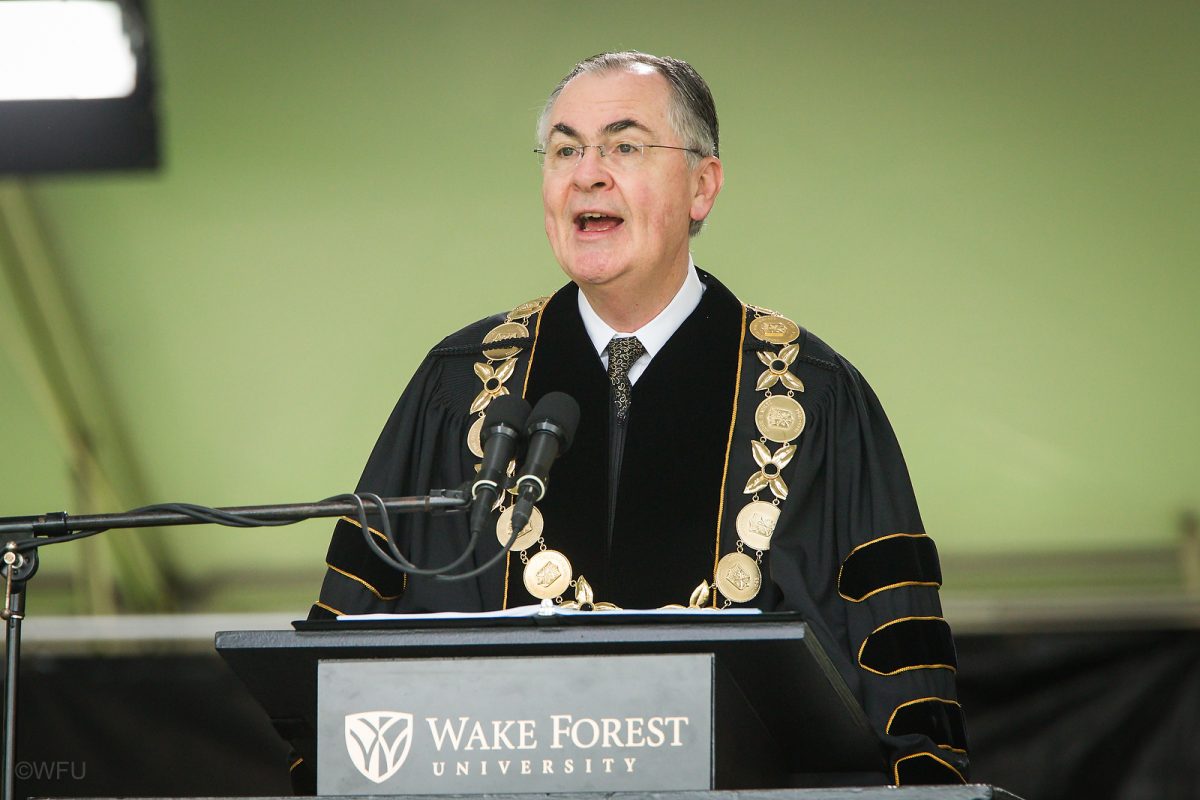

2013: President Hatch

Grit

Wake Forest Commencement Service

By Nathan O. Hatch

May 20, 2013

What a wonderful day this is, Class of 2013, a touchstone in your life. I salute you, and your families, for all that you have accomplished. It has been our privilege to nurture you in this place; to learn with you; and to work together, to build a better, more vital Wake Forest.

Today I want to offer a challenge to you about the road ahead. I am addressing all of you, but particularly those who may have a keen sense of apprehension. You may not have landed the job of your dreams. You may not have been admitted to your first choice of graduate schools. You may have interviewed for a position and not gotten a call back. And for some of you, you are just beginning the arduous task of looking for a job.

This morning I want to talk with you about some surprising studies about what make people successful. All of us are led to believe that intelligence is the key to success: The spoils, we think, generally go to those who are brilliant, to those who have natural leadership talents, to those who are quick on their feet. This morning I am going to suggest an entirely different theory of success, one that offers both encouragement and challenge to us all. My theme today is a character strength called “grit.”

Before she taught psychology at the University of Pennsylvania, Angela Duckworth taught math in middle and high school. She spent a lot of time thinking about something that seemed obvious; students who tried hardest did the best and students who didn’t try very hard didn’t do so well. Duckworth wanted to know: what is the role of effort in a person’s success?

Duckworth’s research focuses on a personality trait she calls “grit.” Grit is “sticking with things over the very long term until you master them.” She writes that “the gritty individual approaches achievement as a marathon; his or her advantage is stamina.”

Duckworth has developed a “Grit Scale.” You rate yourself on a series of about 10 items such as “I have overcome setbacks to conquer an important challenge” and “Setbacks don’t discourage me.”

She has found in a variety of settings that a grit score was the best predictor of success: She found that among West Point cadets, at Ivy League institutions, at the national spelling bee competition, and among underprivileged students seeking to complete college. People with less talent often compensate by working harder and with more determination. The grittiest students, not the smartest ones, often do the best.

Similar themes are evident in the work of Paul Tough, whose books “How Children Succeed” and “Whatever it Takes” challenge the so-called cognitive hypothesis that success depends primarily on cognitive skills. The thesis of these books might be called the character hypothesis: the notion that non-cognitive skills, like persistence, self-control, curiosity, resilience, and grit are more crucial than sheer brainpower to achieving success. “Character is created by encountering and overcoming failure,” Paul Tough suggests. One of his articles is entitled “What if the Secret of Success is Failure?”

Jen Guzman, a young woman who is CEO of a pet food company has made the same point, reflecting on her own career. She notes: “I learned one [important lesson in college] running cross-country, and part of it came from knowing my weakness, which was just pure speed. I developed a strategy. I would stay with the pack for a lot of the race, and then, when it came to the hilly portion, I knew that’s when people tended to give up a little bit because it was the toughest part of the race. So I would actually sprint up the hill, particularly that last 30 percent, when there was that natural reaction to just let go. … When I’m hiring someone, I think, ‘I want someone who’s going to sprint up the hills.’”

This kind of “grit,” or staying power, is important for two reasons. Your generation tends to have interests, many and varied. Many of you have double majored, and maybe thrown in another minor. You have been involved in multiple clubs and organizations, have pursued diverse internships and jobs in the summer, have been great at keeping open all options. Your energy for volunteer work is unprecedented. But you also tend to bounce from one interesting opportunity to another. Your enthusiasms are worthy and intense, but sometimes fleeting. You have not been known for persistence: sticking to something until you really master it.

We live in a world in which our attention spans have been conditioned by this world of 30-second commercials, rapid-fire texts and tweets, and thumbing from one website to the next. More than ever we are passionate about the immediate and the casual. We are wired for distraction.

As you leave Wake Forest today, and take up your first job, or spend a year in volunteer work, or begin graduate school, my advice is to focus on what is set before you. You may think you are overqualified for the task, or that others are pursuing more interesting assignments, or that your assignment is too humdrum and doesn’t inspire your passions.

My advice is that it is better to master something than to dabble in 10 interesting things. Being the faithful steward of a small responsibility will convince others you can be entrusted with larger things. This is not to say you won’t have many different jobs. You will. But when you have a challenge, learn to master it, no matter how difficult. Don’t retreat to something easier, more interesting, or more familiar. Don’t dream about what might be. Learn to sprint up the hills.

Your generation also needs to cultivate a second quality of “Grit:” to understand how to cope with disappointment and failure. The timeless, if uncomfortable truth, is that true strength of character is almost always forged by encountering and overcoming failure.

On this bright and auspicious day, I wish I could promise you graduates the road would always rise up to meet you, that the wind would always be at your back, that the sun would always shine warm on your face. There will be many of those days, I am confident. But there will also be hard days when schooling, or job, or family seem to crumble around you. “Sometimes life hits you in the head with a brick,” Steve Jobs noted in his famous commencement speech at Stanford in 2005. Jobs had revolutionized the world of personal computers in 1984 with the Macintosh, but then the project faltered, and he was fired from the very company he had founded. “It was awful-tasting medicine,” he said, “but I guess the patient needed it.” Jobs concluded that getting fired was actually the best thing that could have happened to him. Why? Because it drove him to reassess everything, to rekindle his creative fire, and to redouble his effort and commitment. It made him resilient.

Why is coming to terms with failure important? Because all of us take turns that seem to go nowhere, launch projects that fizzle, or get caught in organizations into which we do not fit. Particularly in this day and age, no one is exempt from the school of hard knocks. The key is how we respond to such setbacks. Do we lose heart, or do we learn things about ourselves? Do we blame others or do we change our approach? Do we become more skittish or find a way to bounce back, to get back into the saddle?

In this day, the biggest problem with a fear of failure is that we will not take risks. And in this economy, as traditional jobs and careers disappear, you will have to take more risks, become more entrepreneurial. As Thomas Friedman recently stated: “Need a job? Invent it.” You cannot make big bets if you are terrified of failure. Thomas J. Watson, the legendary leader of IBM counseled: “If you want to succeed, double your failure rate.” The point is to lean into disappointment and setback. Become more gritty.

This does not mean that you should lay aside your dreams and ambitions. You should give place to those creative impulses that flourished so bountifully here at Wake Forest. Remember that creativity is not the opposite of sustained hard work. You need to find your passion. But it needs to be yoked to a mindset of persistence and determination. No one was more creative than Thomas Edison, yet he regularly related his insights to a relentless work ethic: “Genius is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration,” he said. “Accordingly a genius is often merely a talented person who has done all of his or her homework.” Another brilliant inventor, Louis Pasteur, put it this way: “Let me tell you the secret that has led me to my goals: My strength lies solely in my tenacity.”

Class of 2013, my challenge today is not for you to lower your sights. Dream big. Make no small plans. But in order to do so, you will also have to ramp up your grit score.

- 2013: Main Story

- 2013: Speaker Gwen Ifill

- 2013: President Hatch

- 2013: Honorary Degrees

- 2013: Programs

- 2013: Commencement Photos

- 2013: Commencement Videos

- 2013: Baccalaureate Photos

- 2013: Baccalaureate Speaker Dr. Carolyn Y. Woo

- 2013: Baccalaureate Videos

- 2013: Senior Profiles

- 2013: Retirees

- 2013: By The Numbers