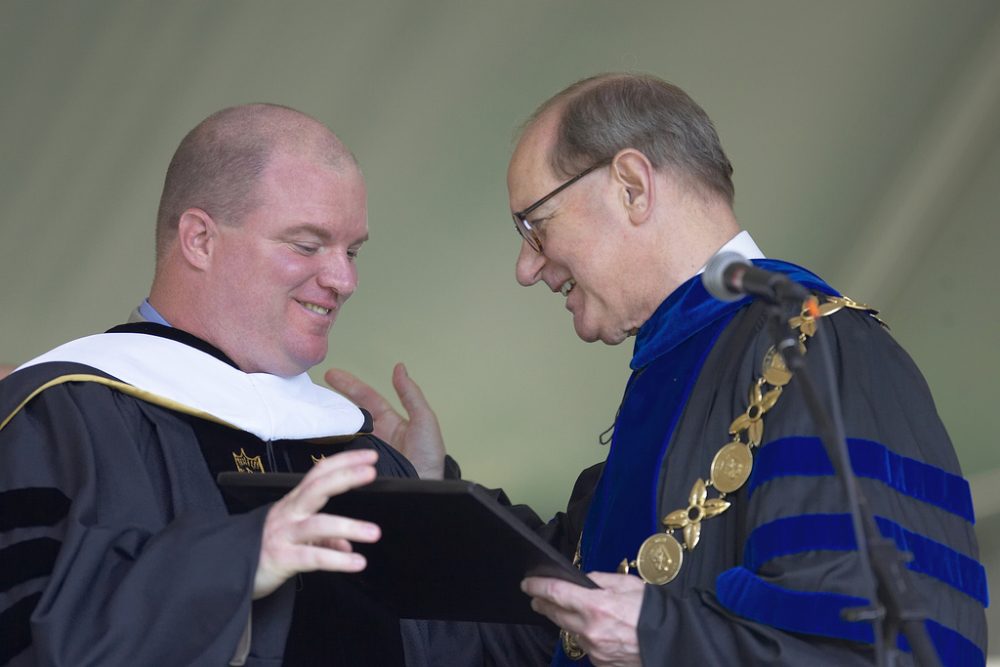

2005: Honorary degree: Piscal

California learning

Mike Piscal (’88) has done his homework, and Los Angeles children are making the grade.

By Scott Holter

From Wake Forest Magazine

When Mike Piscal (’88) launched View Park Preparatory Charter School in 1999, the 240 students in grades K–5 made the venture the second largest startup of its kind in California history. The early success of the school could have led the former English teacher at a Beverly Hills private academy to bask in the fulfillment and put an end to the eighty-hour weeks that had been defining his lifestyle. But Piscal had a dream that was much further-reaching: to provide minority children in Los Angeles with the same educational opportunities as their more than three-quarter million peers throughout America’s second-largest city.

Today there are 560 students in View Park Prep’s three ranks — elementary, middle school and high school — and when a brand new middle school/high school opens this August, there will be room for more than twice that number.

In addition, Piscal has finally seen ground broken on his plans for a $20 million campus in the heart of LA’s African-American community. He would like to open as many as twenty schools — “an education corridor,” Piscal calls it — in a thirty-five-square-mile area between the city of Inglewood and the campus of the University of Southern California. Several grants have already helped pave the way for principals, teachers and staff members, and Piscal serves as View Park’s “mini superintendent.”

The new campus will be located in a complex section of town, but one with unlimited potential. On one side of Crenshaw Avenue, Denzel Washington can often be seen at the new L.A. Cathedral, and the nearby Magic Johnson Theaters have provided a business stimulus to the area. “But on the other side,” Piscal said of the area, “we’re in all the rap songs.”

Piscal, 38, is a New Jersey native who moved to California in 1989 with plans to stay a couple years. But he never moved back. His work with the Inner City Education Foundation (ICEF), a nonprofit organization he founded in 1994 and eventually led to View Park, earned him an honorary degree from Wake Forest at Commencement on May 16.

View Park began for Piscal when he christened a summer program in a church classroom in 1996. Only seven students showed up the first day, but word of mouth brought forty-three additional children by the final day. With not a paycheck in sight, Piscal funded the new school himself to the tune of $50,000 on his personal credit cards. He met his goal to be up and running by 1999, then worked to make certain his students, who are more than 95 percent African-American, learned, tested well and prepare for the future.

In a recent pool of 4,000 students in various high schools in View Park’s South Central Los Angeles location, only 1,700 of them went on to graduate. Only 900 of those 1,700 attended college, with just 258 graduating from college. “That’s $1.7 million per college graduate,” Piscal said. “The whole system is broken. How can this community ever become a working-class community?”

Many parents feel it’s by attending View Park, and Piscal has a waiting list of 5,000 students to prove it. “I finally hired someone just to deal with the waiting list,” he said. Those on the list are chosen by a lottery system, but first attend a series of open houses at the school. There they are told of the expectations for their child: two hours of homework every night, a change in attitude, and a new rule that says school is the number one priority.

“If you sign a contract to come here,” Piscal said, “you have to work with us to help us make these changes in your kids. We form a partnership with the parents, and we get the students to buy into it.”

And apparently students have. The first graduating class of View Park, slated for 2007, recorded the highest test scores among all schools within their Los Angeles Unified School District for 2003–04. “They just need someone to give them a chance,” Piscal said. “It’s similar to something I learned at Wake Forest during an Irish literature course taught by Dillon Johnston. It was a class of students with 4.0s. I was well below three, but he still took me in. He taught me some great values about people, that we all have the talent and gifts and should be given the opportunity to achieve. It’s turned out to be a good lesson.”

Scott Holter is a freelance writer based in Seattle.