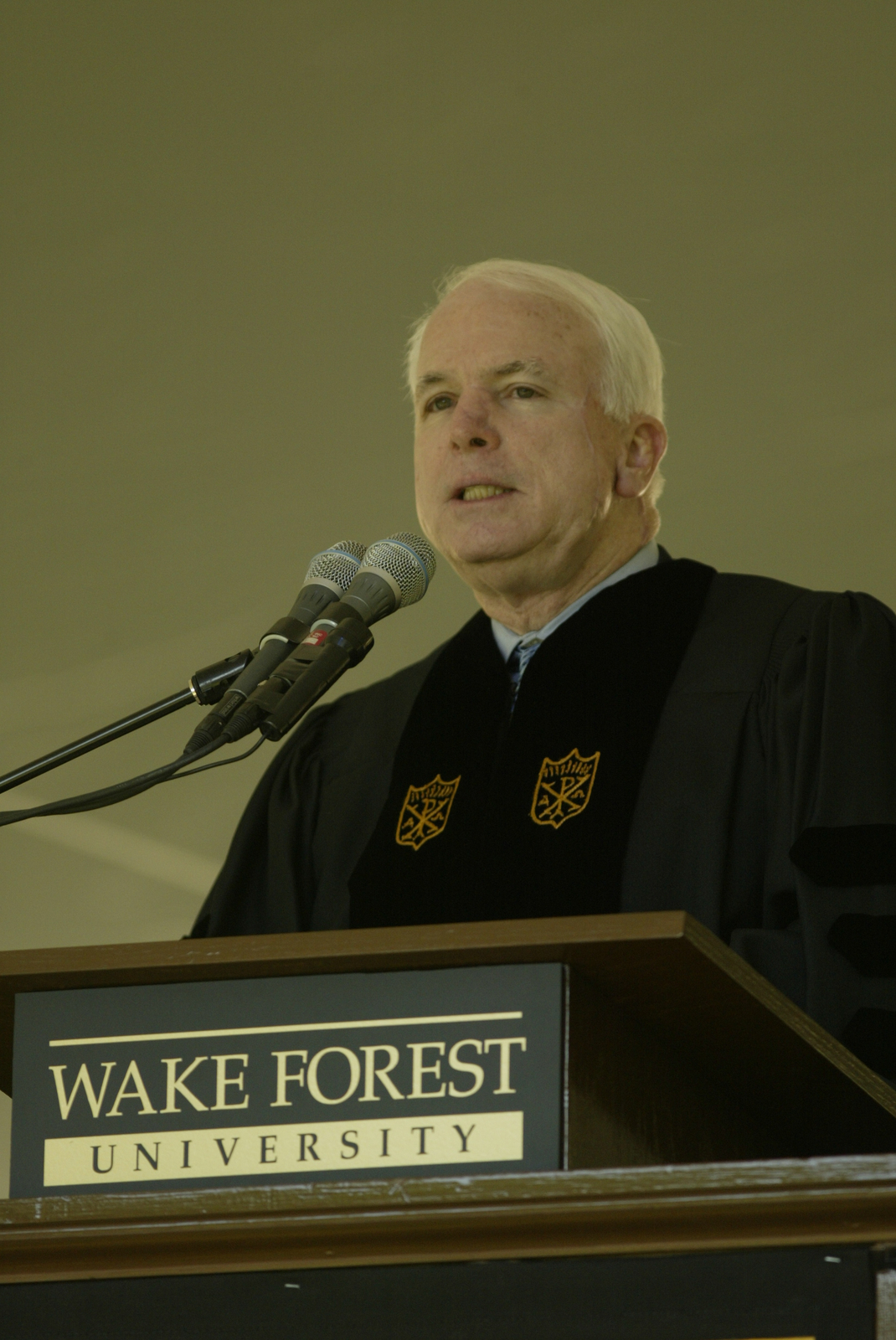

2002: Speaker John McCain

Wake Forest University Commencement Address

By Senator John McCain

Prepared Remarks

May 20, 2002

Thank you, distinguished faculty, families and friends, and thank you, ladies and gentleman of Wake Forest’s Class of 2002. The invitation to give this commencement address is a great privilege for someone who graduated fifth from the bottom in the United States Naval Academy of 1958. To stand here, at this venerable institution, before this distinguished assembly, in full academic regalia, and commend young men and women who are far more accomplished than I was at their age has reaffirmed my life-long faith that in America anything is possible.

If my old company officer at the Academy were here, whose affection for midshipmen was sorely tempted by my less than exemplary behavior, I fear he would decline to hold this university in the high regard that I do.

Nevertheless, I want to join in the chorus of congratulations to the Class of 2002. You have earned it. You have succeeded in a demanding course of instruction from a renowned university. Life seems full of promise. Such is always the case when a passage of life is marked by significant accomplishment. Today, it surely seems as if the whole world attends you.

But spare a moment for those who have truly attended you so well and for so long, and whose pride in your accomplishments is even greater than your own – your parents. When the world was looking elsewhere, your parents’ attention was one of life’s certainties. And if tomorrow the world seems a little more indifferent as it awaits new achievements from you, your families will still be your most unstinting source of encouragement and counsel.

So, as I commend the Class of 2002, I offer equal praise to your parents for the sacrifices they have made for you, and for their confidence in you and their love. More than any other influence in your lives, they have helped make you the success you are today, and might become tomorrow.

I thought I would show my gratitude for the privilege of addressing you by keeping my remarks fairly brief. I suspect some of you might have other plans for the day that you would prefer to commence sooner rather than later, and I will try not to detain you too long.

It is difficult for commencement speakers to avoid resorting to cliches. Or, at least, I find it difficult. Given the great number of commencement addresses that are delivered every year by men and women of greater distinction, greater insights and greater eloquence than I possess, originality can be an elusive quality.

One cliché that seems to insist on my attention is the salutation “leaders of tomorrow,” which is probably uttered hundreds of times by speakers addressing graduating classes from junior high schools to universities. In a general sense, it is an obvious truth. You and your generational cohorts, after all, will be responsible for the future course of civilization. But will you specifically, with all the confidence and vitality that you claim today, assume the obligations of professional, community, national or world leaders? I’ll be damned if I know.

I’m not clairvoyant, and I don’t know you personally. I don’t know what you will become. But I know what you could become. What I hope you will become.

No matter the circumstances of your birth, the very fact that you have been blessed with a quality education from this prestigious university gives you an important advantage as you seek and begin your chosen occupations. Whatever course you choose, absent unforeseen misfortune, success should be within your reach.

All of you will eventually face a choice whether you will become leaders in commerce, government, religion, the arts, the military or any integral part of society. Or will you allow others to assume that responsibility while you reap the blessings of freedom and prosperity without meaningfully contributing to the progress of humanity. Such responsibility, to be sure, is not an unalloyed blessing. Leadership is both burden and privilege. But I don’t believe a passive, comfortable life is worth forgoing the deep satisfaction, the self-respect that comes from employing all the blessings God has bestowed on you to leaving the world a better place for your presence in it.

No one expects you at your age to know precisely how you will lead accomplished lives or use your talents in a cause greater than your self-interest. It has been my experience that such choices reveal themselves over time to every human being. They are seldom choices that arrive just once, are resolved at one time, and, thus, permanently fix the course of your life.

Once in a great while a person is confronted with a choice or a dilemma, the implications of which are so profound that its resolution might affect your life forever. But that happens rarely and to relatively few people. For most people life is long enough and varied enough to account for occasional mistakes and failures.

You might think that this is the point in my remarks that I issue a standard exhortation not to be afraid to fail. I’m not going to do that. Be afraid. Speaking from experience, failing stinks. Just don’t stop there. Don’t be undone by it. Move on. Failure is no more a permanent condition than success. “Defeat is never fatal,” Winston Churchill observed. “Victory is never final. It’s courage that counts.”

It is courage that counts. And it counts much more when you employ it on behalf of others, for purposes beyond personal advantage. In this country, use your courage, as you should use your liberty, to reaffirm human dignity.

Theodore Roosevelt is one of my political heroes. The “strenuous life” was T.R.’s definition of Americanism, a celebration of America’s pioneer ethos, the virtues that inspired our belief in ourselves as the New Jerusalem, bound by sacred duty to suffer hardship and risk danger to protect the values of our civilization and impart them to humanity. “We cannot sit huddled within our borders,” he warned, “and avow ourselves merely an assemblage of well-to-do hucksters who care nothing for what happens beyond.”

His Americanism was not fidelity to a tribal identity. Nor was it limited to a sentimental attachment to our “amber waves of grain” or “purple mountains majesty.” Roosevelt’s Americanism exalted the political values of a nation where the people are sovereign, recognizing not only the inherent justice of self-determination, not only that freedom empowered individuals to decide their destiny for themselves, but that it empowered them to choose a common destiny. And for Roosevelt that common destiny surpassed material gain and self-interest. Our freedom and industry must aspire to more than acquisition and luxury. We must live out the true meaning of freedom, and accept “that we have duties to others and duties to ourselves; and we can shirk neither.”

Some critics, in his day and ours, saw in Roosevelt’s patriotism only flag-waving chauvinism, not all that dissimilar to Old World allegiances that incited one people to subjugate another and plunged whole continents into war. But they did not see the universality of the ideals that formed his creed.

A few years ago, I read an account of an Irishman’s attempt to make the first crossing of the Antarctic on foot. In August 1914, Sir Ernest Shackleton placed an advertisement in a London newspaper.

“MEN WANTED FOR HAZARDOUS JOURNEY. SMALL WAGES, BITTER COLD, LONG MONTHS OF COMPLETE DARKNESS, CONSTANT DANGER, SAFE RETURN DOUBTFUL. HONOUR AND RECOGNITION IN CASE OF SUCCESS.”

Twenty-eight men answered the ad and began a twenty-two month trial of wind, ice, snow and endurance. Photographs of the expedition survive today produced from plate glass negatives that one of Shackleton’s men dove into freezing Antarctic waters to rescue from their sinking ship. The deprivations these men suffered are almost unimaginable. They spent four months marooned on a desolate ice-covered island before they were rescued by Shackleton himself. They endured three months of polar darkness, and were forced to shoot their sled dogs for food. Their mission failed, but they recorded an epic of courage and honor that far surpassed the accomplishment that had exceeded their grasp. When they returned to England, most of them immediately enlisted to fight in World War I.

Years later, Shackleton looked back on the character of his shipmates. He had had the sublime privilege of witnessing a thousand acts of unselfish courage, and he understood the greater glory that it achieved. “In memories we were rich,” he wrote. “We had pierced the veneer of outside things.”

I thought when I read it that there, in that memorable turn of phrase, was the Roosevelt code. To pierce the veneer of outside things, to strive for something more ennobling than the luxuries that privilege and wealth have placed within easy reach. For the memories of such accomplishments are fleeting, attributable as they are to the fortuitous circumstances of our birth, and reflect little credit on our character or our nation’s.

Nationalism is not intrinsically good. For it to be so a nation must transcend attachments to land and folk to champion universal rights of freedom and justice that reflect and animate the virtues of its citizenry. Racism and despotism have perverted many a citizen’s love of country into a noxious ideology. Nazism and Stalinism are two of the more malignant examples. National honor, no less than personal honor, has only the worth it derives from its defense of human dignity. Then, and only then, are they virtues in themselves. Many a patriotic German sought honor in doing one’s duty to the furher and fatherland. History and humanity, not to mention a just God, scorn them for it. Prosperity, military power, a well-educated society are the attainments of a great nation, but they are not its essence. If they are used only in pursuit of self-interest or to serve unjust ends they degrade national greatness. Nazi Germany was temporarily a powerful nation. It was never a great one.

We are not a perfect nation. Prosperity and power might delude us into thinking we have achieved that distinction, but inequities and challenges unforeseen a mere generation ago command every good citizen’s concern and labor. But what we have achieved in our brief history is irrefutable proof that a nation conceived in liberty, will prove stronger and more enduring than any nation ordered to exalt the few at the expense of the many or made from a common race or culture or to preserve traditions that have no greater attribute than longevity.

For all the terrible suffering they caused, the attacks of September 11 did have one good effect. Americans remembered how blessed we are, and how we are united with all people whose aspirations to freedom and justice are threatened with violence and cruelty. We instinctively grasped that the terrorists who organized the attacks mistook materialism as the only value of liberty. They believed liberty was corrupting, that the right of individuals to pursue happiness made societies weak. They held us in contempt. Spared by prosperity from the hard uses of life, bred by liberty only for comfort and easy pleasure, they thought us no match for the violent, cruel struggle they planned for us. They badly misjudged us.

What ensures our success in this struggle is that our military strength is only surpassed by the strength of our ideals, and our unconquerable love for them. Our enemies are weaker than we are in arms and men, but weaker still in causes. They fight to express an irrational hatred of all that is good in humanity, a hatred that has fallen time and again to the armies and ideals of the righteous. We fight for love of freedom and justice; a love that is invincible. We will never surrender. They will.

My friends, if you want to know a happiness far more sublime than pleasure lend your talents, your industry, your courage to the service of our ideals. For in their service, you will discover their authentic meaning, the broad sweep of their virtue, more than you can learn from the lessons of history, the instruction of civic textbooks, or from the advice of any commencement speaker.

Take your place in the enterprise of renewal, give your counsel, your labor, and your passion in your time to advancing the universal ideals upon which this nation was founded. Prove again, as those who came before you proved, that a people free to act in their own interests will perceive their interests in an enlightened way, will live as one nation, in a kinship of ideals, and make of our power and wealth a civilization for the ages, a civilization in which all people share in the promise of freedom.

All lives are a struggle against selfishness. All my life I’ve stood a little apart from institutions I willingly joined. It just felt natural to me. But if my life had shared no common purpose, it wouldn’t have amounted to much beyond eccentricity. There is no honor or happiness in just being strong enough to be left alone.

I’ve made plenty of mistakes. And I have many regrets. But only when I have separated my interests from my country’s ideals are those regrets profound. That is the honor and the privilege of public service in a nation that isn’t just land and ethnicity, but a noble idea and cause, a champion of human dignity. Any benefit that ever accrued to me on occasions in my public life when I perceived my self-interest as unrelated to the cause I was sworn to serve, has been as fleeting as pleasure, and as meaningless as an empty gesture.

In America, our rights come before our duties. We are a free people, and among our freedoms is the liberty to not sacrifice for our birthright. Yet those who claim their liberty but not the duty to the civilization that ensures it, live a half-life, having indulged their self-interest at the cost of their self-respect. The richest man or woman, the most successful and celebrated Americans, possess nothing of importance if their lives have no greater object than themselves. They may be masters of their own fate, but what a poor destiny it is that claims no higher cause than wealth or fame.

Should we claim our rights and not our duty to ensure their blessings to others, whatever we gain for ourselves will be of little lasting value. It will build no monuments to virtue, claim no honored place in the memory of posterity, offer no worthy summons to other nations. Success, wealth, celebrity gained and kept for private interest is a small thing. It makes us comfortable, eases the material hardships our children will bear, purchases a fleeting regard for our lives, yet not the self respect that in the end matters most. But sacrifice for a cause greater than your self-interest, and you invest your life with the eminence of that cause, your self-respect assured.

When I was a young man, I thought glory was the highest ambition, and that all glory was self-glory. My parents tried to teach me otherwise, as did the Naval Academy. But I didn’t understand the lesson until later in life, when I confronted challenges I never expected to face.

In that confrontation, I discovered that I was dependent on others to a greater extend than I had ever realized, but that neither they nor the cause we served made any claims on my identity. On the contrary, they gave me a larger sense of myself than I had before. And I am a better man for it. I discovered that nothing in life is more liberating than to fight for a cause that encompasses you, but is not defined by your existence alone. And that has made all the difference, my friends, all the difference in the world.

Those days were long ago. But not so long that I have forgotten their purpose and their reward. This is your moment to make history. This is your chance to pierce the veneer of outside things, to live out the authentic meaning of freedom.

I don’t know how far humanity will progress in this century, but I expect great things, great things indeed. I envy you for the discoveries you will experience that I can only imagine, but will not see. Be worthy of your times and your advantages. Your opportunity is at hand. Make the most of it.

Will you be tomorrow’s leaders? I don’t know. But I would be proud and grateful if you were.

Congratulations and good luck.