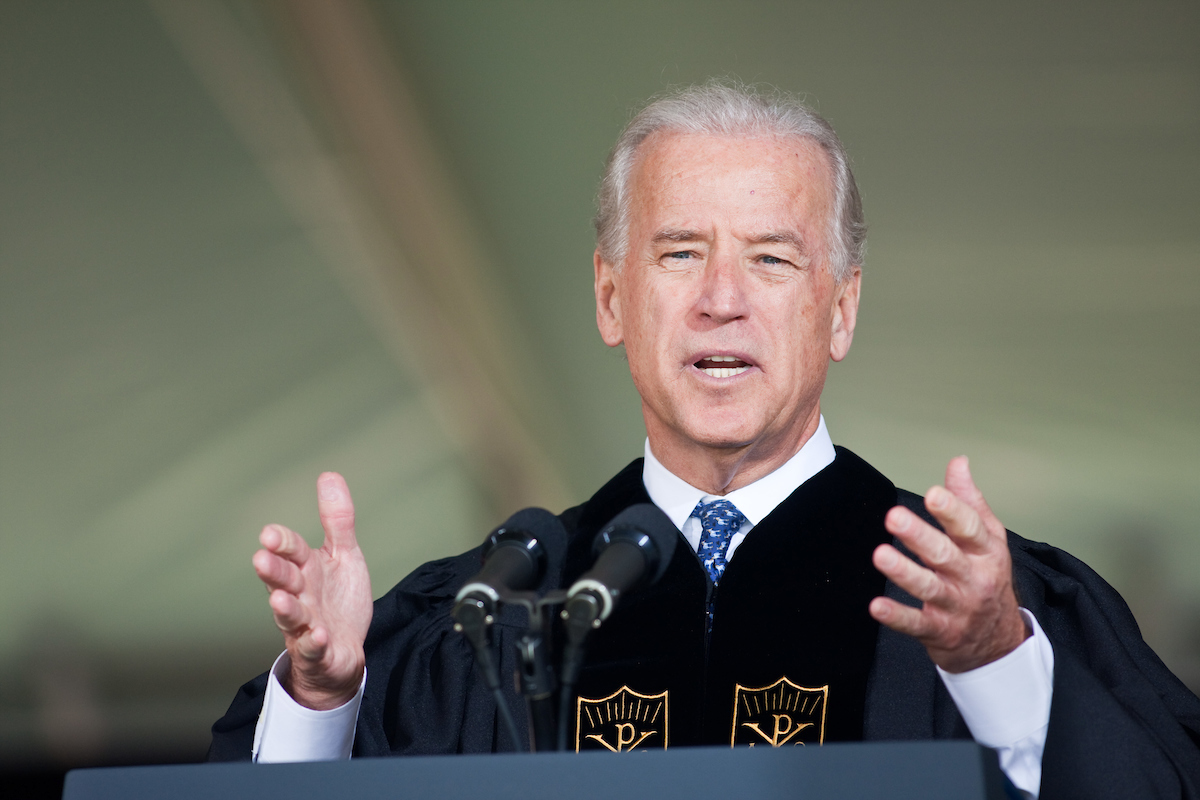

2009: Speaker Joe Biden

Vice President Joseph Biden delivered the Commencement Address at Wake Forest University on Monday, May 18, 2009. His introduction was by President Nathan O. Hatch.

[REMARKS BY THE VICE PRESIDENT AT WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY, AS PREPARED]

Thank you very much, Mr. President. Thank you very much. I say to all the faculty, this will be painless. They have felt like — I suspect they’ve heard a hundred — all the commencements since the beginning of the school.

But I’m honored to be here. It was a long trip from that end of your mall to this end. Last time I was here you were kind enough, many of you students, to listen to the case I was making. And I am honored that notwithstanding the fact you’ve heard me once, you’ve invited me back a second time. I thank you.

Mr. President, you were suggesting that you arrived at the same year as this graduating class. Well, if I’m not mistaken, you rode into the ceremony on the famous Demon Deacon gold motorcycle, and they drew up in vans with their parents moving furniture.

So I thought I should try to replicate something along the lines that you did when you arrived, and I had planned on driving my ’67 Corvette up the middle of this area here. But the Secret Service said they wouldn’t let me do it. But notwithstanding the fact that my ride’s been slightly different, I’m delighted to be here.

And I congratulate all those graduating in the class of 2009. What a great day for you all. You deserve a round of applause.

And being the father of three children, all of whom unfortunately listened to me when I said early on when they were in high school, any school you can get into, I’ll help you get there. Well, undergraduate and graduate schools later, for three of them, you know understand why I was listed as the second poorest man in the Congress, literally.

So I say to all you parents, today is payday. You get a raise today. Don’t encourage them to go to graduate school, because it keeps up. To all the parents, I know your sons and daughters, grandsons, granddaughters, husbands, wives — I know that your student understands they would not be sitting here today but for your support.

And it’s a real honor for me to be here today. But in a sense, it’s a bittersweet honor, tempered by the sadness that I feel about a man who was originally scheduled to be your commencement speaker, a friend of mine, Tim Russert.

You see, Tim and I came to Washington four years apart, but from similar backgrounds — he came from a blue collar neighborhood in Buffalo, and I came from a working-class neighborhood in Scranton, Pennsylvania. But we shared something in common — even though we didn’t know each other at the time — we grew up in neighborhoods where we never had to wonder whether or not we were loved.

We were both raised by parents who had an absolute conviction, an absolute belief in the promise of this country, and that even two kids from similar backgrounds could do anything they wanted. We grew up in a time when our parents told us, and meant it and believed it, even though they were of modest means, that if we worked hard, played by the rules, did what we were supposed to, loved our country, there wasn’t a single thing we couldn’t do.

One of the reasons why Barack and I set off on this journey was to sort of re-instill that confidence in a new generation of parents who played by the rules, but it didn’t quite work out for them. It didn’t quite work out.

I remember leaving for Washington as a 29 year-old United States Senator. I was elected before I was eligible to take office. And having run and won with an absolute certitude that I was capable of doing the job, never doubting — because of the way I was raised — that I could do this. And I remember when I first got there, the people who became my friends, because my colleagues, the average age if I’m not mistaken, Mr. President, was about 64 years of age. And although I had very good relationships with my colleagues, I was the kid.

And so I literally became friends with, socialized with, the staffs of my colleagues — in a literal sense — I had just lost my wife and daughter. I was single. I had very little in common with the men and women with whom I was serving. And four years into my time there, I had met Tim Russert. And we worked for a man who came four years after me, but nonetheless was still my mentor, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, the senator from New York.

And we were talking one day in the Senate about our backgrounds and how we were so certain that we were raised thinking we could do anything — until we each got to Washington. And I shared a story with him about how, when I got here, how, for the first time in my life, I was somewhat intimidated by the depth and scope and the background of the people I was working with — people like William J. Fulbright and Jacob Javits and former governor Averell Harriman, who was sort of the intellectual dean of the — Al Hunt will remember this — Katharine Graham, who was sort of the Grand Dame of Washington. And I remember going to these functions early on and thinking, I’m not sure I belong here.

And Tim related a similar story, which has subsequently been told many times, that he wrote about in his book. He said when he first got to Washington, working for Senator Moynihan, he thought that things weren’t going quite the way he thought. He said, when I first got to D.C. and I walked into Senator Moynihan’s office, I was completely overwhelmed by the intellectual firepower of the people he had working for him, as well as his intellectual firepower — Rhodes scholars, Marshall scholars, professors, people with Ivy League degrees, people with significant backgrounds.

And he said one day after attending a staff meeting, he walked into Senator Moynihan’s office, and he told him — he said, “Senator, maybe I don’t belong here. Maybe I should leave.” And you know what the senator said to him, according to Tim? And it sounds like Pat. He said, “Tim, what they know, you can learn. What you know they can never learn. So he stayed. And he went on to host “Meet the Press” and head up NBC’s political coverage. He changed the nature of the way major events and major figures were covered. His integrity, his toughness, his fairness was legendary.

Eventually he became a vitally independent, nationally respected and universally beloved voice in Washington, trusted by everyone who went before him. You knew you had to be prepared. You knew you had to have your A game on. But you also knew he’d never belittle you, he’d never take a cheap shot. He was completely contrary to some of the culture that prevails — and still prevails — in the town I work.

And along the way, Tim Russert, enlivened and enriched our debate. He gave it meaning. He gave it substance. Along the way he made all of our lives richer. And Tim’s wife, Maureen, is here today at the appropriate moment to accept an honorary degree in Tim’s stead. And I know Tim is looking down, Maureen, smiling at you with that pride that his face lit up with every time he talked about you. And he’s likely sitting on a big gold motorcycle while he’s watching.

So folks, I know how proud he’d be as well of you, both for what you have already accomplished and the expectations we have of all of you as to what you’re going to accomplish.

At the turn of the 20th century, William Allen White — a writer, a politician, a national spokesman for middle class values — summed up perfectly the optimism I feel for the future. He said, “I’m not afraid of tomorrow, for I’ve seen yesterday, and I love today.”

Well, I love today and one of the reasons I do is because of all of you. I believe so strongly, as you may recall when I was here in October, not in you particularly but your generation, that I don’t have a single doubt in my mind we’re on the cusp not only of a new century but a new day for this country and the world. I know what you do — there’s not a single thing you’re going to be unable to accomplish.

Your generation is off fighting wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Your generation is volunteering in record numbers. Your generation voted and turned out in a way that you literally dictated the outcome of this last election. Your generation gives such strong hope that we’ll not only survive today as some pundits argue we may not, but that we will thrive tomorrow. And I believe you believe as I do — that this is all within our grasp.

I know one other thing for certain as well. No graduating class gets to choose the world they graduate into. Every class has its own unique challenges. Every class enters a history that up to that point has been written for them. And your generation is no different. But what is different about your generation is the chance that each of you has to take history into your own hands and write it larger.

If anyone gets to choose the circumstances in which they graduate, I suspect almost all of us would choose your present circumstance. Your generation’s opportunities are greater than any generation in modern history — not because you’re about to graduate into a nation of ease and luxury, but because you’re about to graduate into a point in history where everything is going to change no matter what you do, but you can affect the change.

When I graduated in the ’60s, it was a time of turmoil. I graduated from undergraduate school in ’65, law school in ’68. It was a time of turmoil, of change, of idealism, of war, of violence, of chaos, Vietnam, civil rights, women’s rights, JFK, MLK, RFK, black power, flower power. These were our times. That was our history. But still, by the time I graduated, my generation’s main goal was simply to restore the order and the hope of an earlier part of that decade; a part of the decade before John Kennedy was assassinated. Our charge was to try to regain control of a world that seemed to beginning to spin out of control.

The semester that I graduated from law school, Johnson stepped down. Two weeks later, Martin Luther King was assassinated. Three days before I walked across the stage, RFK was assassinated. The Tet Offensive occurred earlier in the year, making clear that there was no light at the end of the tunnel. But nonetheless we graduated with the expectation that we could restore order.

But today, with all the difficulties you face, you graduated into a moment where your opportunities are much greater. And your charge is not to restore anything but to make anew. You too are graduating in a world of anxiety and uncertainty. You’re going to walk across this stage without knowing for certain what’s on the other side. Good jobs are hard to find, two wars are being waged on the other side of the globe, there’s a global recession, a planet in peril, and a world in flux.

Throughout the span of history though, only a handful of us have been alive at times when we can truly shape history. Without question, this is one of those times, for there’s not a single solitary decision confronting your generation now that doesn’t yield a change from non-action as well as action.

We’re either going to fundamentally revive our economy and lead the way to the 21st century, or we’re going to fall behind and no longer be the leader of the free world in the 21st century. We’re either going to fundamentally revamp our education system, or remain 17th in the world of graduates from college, and in the process lose our competitive edge and find it difficult to have it restored. We’re either going to fundamentally change our energy policy or remain beholden to those who pose the biggest threats to our security. We’re either going to revive and reverse climate change, or literally drown in our indifference.

Folks, we’re either going to fundamentally change the course of history, or fail the generations that come after us, because change will occur. Non-action is action, unlike most generations.

I’ve served with eight Presidents. Most Presidents are able to say, of the four or five issues that are before me, I’ll put aside three and we’ll get to them later, knowing the status quo ante will pertain. There’s not a single issue on this President’s plate that will not yield a change — just merely by ignoring it, it will change.

I call, and others call, these moments in history, as rare as they are, inflection points. Remember your physics class? You’re driving along in an automobile and you move the wheel slightly to the left or right, and you send the car careening in the direction that absent another change will end up a significant distance from where you were aimed. That’s an inflection point.

William Butler Yeats was right. Tim used to always kid me about quoting Irish poets. He thought I quoted them because I was Irish. That’s not the reason. I quote Irish poets because they’re the best poets.

There’s a great line in one of Yeats’ poems about the first rising in Ireland. It’s called Easter Sunday, 1916. And the line is more applicable to your generation than it was to his Ireland in 1960. And he said: All changed, changed utterly. A terrible beauty has been born.

When I graduated, all had not changed utterly yet. Today, it has. And in the last 12 to 15 years, a terrible beauty has been born. It’s a different world out there than it has been any time in the last millennia. But we have an opportunity to make it beautiful, because it is in motion. We have an opportunity to change it. But absent our leadership, it will continue to careen down the path we’re going now. And that could be terrible. That, folks, is an inflection point.

Doing nothing, or taking history into our own hands and bending it, bending it in service of a better day. So embrace the moment. Don’t shy away from it. You know how I feel. I’m confident you must feel the same way. For one thing, I’ve learned is that in the face of struggle, there is a greater risk in accepting a situation we cannot sustain. Does anybody think we can sustain our present energy policy? Does anybody think we can sustain our present economic policy? Does anyone think we can sustain our present educational policy? Does anyone think we can sustain our present environmental policy?

It is to not sustain — we know we cannot sustain the way we’re going now. So it’s time to steel our spines, and embrace the promise of change, even though we cannot guarantee exactly what that change will bring. And the good news is that’s exactly what the country did when they voted this last November. They voted for change, not certain what it would mean, but convicted in the assumption that we cannot sustain the path we’re on.

America embraced the promise of change. It took a chance. The truth is no single individual or circumstance can determine when one of these inflection points will occur. What triggers such moments is the accumulation of so many forces over a sustained period of time that it’s difficult to identify. But individuals willing to steel their spines do determine what moments, what such moments will produce. And you are those individuals.

As corny as it sounds, this really is your moment. History is yours to bend. Imagine. Imagine what we can do. Imagine a country where within a decade, 20 percent of our energy is from renewable sources, where we’re no longer dependent on unstable dictatorships for our energy.

Imagine a country that invests in every child in America where you’ve learned we should be investing at age three instead of six, where every single qualified — young man or woman qualified to go to college is able to go to college regardless of their financial circumstances.

Imagine a country where health care is affordable and available to every single American, where American business can compete again because they don’t bear all the cost; where we can once again gain control of our fiscal future, which is being drowned by the cost of health care. Imagine a country where our carbon footprint shrinks to nothing, and we set an example for the whole world to follow.

Just imagine. Imagine a country brought together by powerful ideas, not torn apart by petty ideologies. Imagine a country built on innovation and efficiency, not on credit default swaps and complex securities. Imagine a country that values science again. Imagine a country that lifts up windows of opportunity, doesn’t slam them shut. Just imagine. Imagine a country where every single person has a fighting chance; a country that once again leads the world by the power of our example and not merely by the example of our power.

Graduates, that’s all within our power. It’s all capable of being done. Some of you may think, like your parents, I may be too optimistic. I say, no, I’m not optimistic — I’m realistic. Despite the uncertainty, I was optimistic when I graduated in 1965 and again in ’68, when I got to the Senate when I was 29, as a 29-year-old kid. But I must admit if anyone had told me back then that my idealism and my optimism would be even greater in the year 2009 I would have told you, you’re crazy. But as God as my witness, it is — because we’re at this moment.

And there’s really good reason for my optimism. As a student of history, it’s the history behind me and the people in front of me that give me such a degree of optimism; it’s Grace Johnson graduating today, who recently won an award for completing more than 300 hours of AmeriCorps service in one year. It’s Nadine Minani, who’s about to walk across the stage after losing her mother in the Rwandan genocide when she was only eight years old. It’s about Aaron Curry, a scrawny freshman linebacker — (laughter) — recruited by only two schools, who worked his rear end off, became a top five pick, and is walking off this stage into an opposing NFL backfield. Aaron, I heard you wanted to go to law school — you were considering going to graduate school. I also heard that your fellow draftees have taken up a collection encouraging you to go. So I’m sure there’s a scholarship there if you want it.

It’s the 17 of you heading out to Teach for America. And, finally, it’s Fred Hastings, who I got to meet, who came to Wake Forest more than a half a century ago, left to join the Army before he could finish. Years ago, he saw his son graduate from Wake and decided — hell, if he can do it I can do it. And he’ll be walking across the stage, and on Thursday will be his 77th birthday. Give him a round of applause. He deserves it. I asked him if his son paid for his education. I didn’t get an answer.

In so many ways, you’re already bending history. You’re teaching our kids. You’re saving our planet. You’re enriching communities the world over. You’re connecting to each other in ways that most of us could never have dreamed of when we graduated, and using those connections to unite our global community, to deepen our understanding of the world around us. You are emblems of the sense of possibility that’s going to define our new age.

In the past, it’s always been older generations, my generation speaking — standing up here at commencements telling the next generation the ways of the world, trying to make sure you follow in our footsteps. Well, graduate, I’ll have to admit, it’s a lot different today. You’ve flipped the script, as you might say. You’re, quite simply, teaching us.

And I am here to tell you — tell you all — that even Tim would be happy to know what you know we can learn. Just keep teaching us. What you know we can learn, and we have to learn.

Just as with each of those rare generations that found itself at an inflection point in history, it’s within our power to shape our history, to bend it in the right direction. We can’t make a utopia, but we sure can make it a lot more beautiful. This is not bravado. This has been the history of the journey of America — never, ever, ever, ever, ever, ever, never have the American people let their country down at rare moments, similar moments in our history. And it’s a journey we’re all going to take together.

So for those who tell you that we’re doing too much now in the administration — or you’re seeking too much — be smart enough not to listen. And for those who say not to try, be naive enough to give it a shot, to give it a shot. And for those that say it’s impossible, point them to your professor, Maya Angelou.

“We must confess,” she writes, “that we are the possible. We are the miraculous, the true wonders of the world. That is when, and only when, we come to it.” Well, you’ve come to it. I look out there at the caps and the gowns; I look at a university so miraculous in its history, a class so electric in its diversity. I look at it all, and I see so clearly what Maya meant.

You are the possible. That is not hyperbole. You are the possible. We are the possible. And we have at once finally come to it. So seize it. Seize it. Because if you do not, it will slip from our grasp and determine the world you live in while you sit idly by.

Thank you all so much. Congratulations once again. And may God bless America, and may God protect our troops. Thank you.

Joe Biden Audio

- 2009: Main Story

- 2009: Speaker Joe Biden

- 2009: President Hatch

- 2009: Press release

- 2009: Honorary degrees

- 2009: Retiring: Bob Beck

- 2009: Retiring: Ed Hendricks

- 2009: Retiring: Fred Howard

- 2009: Retiring: Pete Weigl

- 2009: Retiring: David Shores

- 2009: Retiring: Steve Ewing & Don Robin

- 2009: Senior Profiles

- 2009: Commencement Photos

- 2009: Baccalaureate Photos

- 2009: Video: Ceremony

- 2009: Baccalaureate

- 2009: By the numbers

- 2009: Programs