2008: Retiring: Andronica

Latin lover

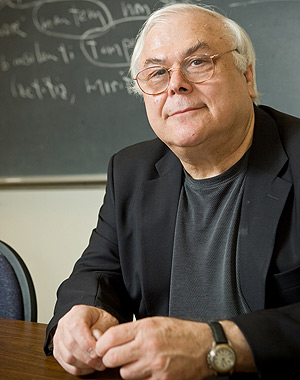

“Andy” Andronica looks back on a life of doing what the Romans did and as one to whom it was all Greek

By David Fyten

Office of Creative Services

Posted May 19, 2008

For John Andronica, the passage of years has been occhiata dalla finestra — a “glance out the window,” as the Italians would say. Fitting he should choose an Italian expression as he reflects upon his long — but to him, all too brief — tenure as professor and chair of classical languages. Not only was he born of Italian lineage, he was literally raised to study and teach Latin, Greek and the glories of ancient Mediterranean civilizations.

“Andy” (as everybody, including himself, calls him) is using the occasion of his retirement this spring to watch the passing of a veritable Grand Canal of memories. From the evening in 1971 when famed American expatriate poet Ezra Pound, just months from his death, sat in Wake Forest’s newly acquired house in Venice watching a traveling British theatrical troupe perform three one-act plays by Harold Pinter; to the student whose research into the species of snake that might have killed Cleopatra impressed the committee that was reviewing her medical school application; the recollections, when listened to, assume a kind of autumnal hue evocative of the unique light that bathes his beloved city of canals.

Andy was born and raised in the Boston area, and he remains a prototypical New Englander in many respects, still possessing that distinctive accent that makes no distinction between a pair of tan slacks and the unlocking devices with which one starts an automobile. But in most respects he has become an inveterate Southerner, especially in his embrace of Wake Forest’s traditions and its culture of graciousness and collegiality.

From elementary school through high school, Andy attended Boston Latin, known widely for its rigorous classical curriculum. He began studying Latin in the sixth grade and Greek in the ninth, and “when I was 11, 12 or 13 and thought there might be something better to do than declensions and conjugations, my parents thought otherwise.”

After graduation he enrolled at Holy Cross, a Jesuit college in Worcester so traditional that chapel attendance was still compulsory. For two years he was a pre-med student, all the while continuing his classical languages studies. “I guess you could say I backed into an academic career. I loved Latin and Greek and thought there surely would be people out there who would be interested in the same things.”

After completing a master’s degree at Boston College and a doctorate at Johns Hopkins University, Andy sought a teaching job at a small liberal arts college that valued classical studies. In 1969 he accepted Wake Forest’s offer to join its classical languages department, then headed by Carl Harris and the venerable Cronje Earp. Much to his surprise three years later, he was appointed as chair while concurrently being asked to direct the first year of studies at a Venetian palazzo — soon to be named Casa Artom — that had housed the U.S. Consulate and was being transferred to the University.

“I still recall that year in vivid detail,” Andy says. “The day we [he, wife Grace, and their two small children] returned to Venice after the Christmas holidays, the place was locked and bolted from the inside, with no access otherwise. We called the local caretaker, a holdover from the American Consulate days, who had to climb a ladder and scale a garden wall to let us in.”

Besides Pound, the memorable personalities they encountered that inaugural year included next door neighbor Peggy Guggenheim, the eccentric heiress and art patron whose odd habits and behaviors made for many moments of amusement as well as consternation.

Then there was the house’s oil furnace. “It was against the law even then to burn oil because of air pollution, but it was not a problem for us since our oil-fired furnace rarely worked. In winter — and it can get quite cold in Venice then — the students would walk to the fruit and vegetable markets and scavenge wooden crates, which we would burn for heat in the fireplace. To keep warm at night, we’d light the stove in the kitchen and sleep huddled together.

“The students couldn’t speak Italian, so Grace [who, like Andy, is of Italian extraction] taught it to them on a not-for-credit basis. I taught a three-course load while directing our program and dealing with an administrative system that required payment of different utility bills in person at locations at opposite ends of the city. It was one hassle and improvisation after another.

“But I’ll tell you: not one of the students that year left as the same person he or she was when they arrived,” he adds. “They had the wonderful experience of living and studying abroad, and the challenges they faced and the fixes they got into and had to get out of on their own allowed them to grow and mature beyond their years.”

Despite — or perhaps because of — those initial challenges, Andy adores Casa Artom and Venice. He has returned four times in an official capacity — three times as director and once to oversee the transition of a summer program for the law school in 2000. And despite — or, again, because of — the challenges of chairing a department as a junior faculty member and the lack of course-load reductions that chairs of larger departments typically enjoyed, he has directed the department for 28 of his 39 years at the University.

The classical languages department today has four tenured faculty members in Latin and Greek plus a fifth non-tenured member who teaches Arabic in a new program administered by the department. Andy can recount a wealth of anecdotes about the many exceptional students he’s had over the years. One of his favorite stories is about a young woman who enrolled in his first-year seminar on Cleopatra and became intrigued by the mystifying circumstances surrounding the queen’s death. The student did some original research and postulated the type of venomous snake that might have killed the Queen of the Nile. Later, she made a favorable impression by recounting her findings to a committee that was interviewing her for admission to its medical school. Not coincidentally, perhaps, she was accepted.

One might surmise that attraction to classical languages and studies would be waning in this age of the here and now, but Andy says the opposite is the case. “We have approximately 30 students who are majors or minors compared with the five or six majors we had when I first arrived,” he says. “At that time many of the majors were interested in a teaching career, but today most are looking toward careers in one of the health professions or another profession. All, though, are drawn to the challenge and opportunity to engage in ongoing dialogue with the great minds and issues of the past in ways that might not be possible otherwise. We have wonderful students, and the caliber of applicants Wake Forest attracts in general means that many come with backgrounds and interests in Latin, Greek and classical studies.”

Andy is skilled in virtually all of the construction trades — carpentry, electrical work, plumbing, you name it — and he intends to put them to use as a Habitat for Humanity volunteer in retirement. He and Grace (who was the real estate agent for more than a few arriving and departing members of the faculty and staff over the years) plan to do a lot of traveling as well.

It seems an altogether fitting coda to the life of one so conversant with the building and spreading of Western civilization’s noblest institutions and aspirations. Docere est discere: studium permanet — “To teach is to learn: the pursuit remains constant.”

- 2008: Main story

- 2008: Speaker E.J. Dionne Jr.

- 2008: Press release

- 2008: Honorary Degrees

- 2008: Retiring: Andronica

- 2008: Retiring: Kerr

- 2008: Retiring: Knott

- 2008: Retiring: Mandelbaum

- 2008: Retiring: Bowman Gray campus

- 2008: Senior oration: Cowan

- 2008: Senior oration: Haley

- 2008: Senior oration: Lazazzero

- 2008: Senior profile: Carroll

- 2008: Senior profile: Catanese

- 2008: Senior profile: Cooper

- 2008: Senior profile: Frazier

- 2008: Senior profile: Lopez

- 2008: Senior profile: McGuire

- 2008: Senior profile: Mullikin

- 2008: News: Beshara

- 2008: News: Chauvenet

- 2008: News: Fulbrights

- 2008: News: Jones

- 2008: News: Phi Beta Kappa

- 2008: News: Scott

- 2008: News: Warren

- 2008: Commencement Photos

- 2008: Video: Speaker

- 2008: Video: Ceremony

- 2008: Video: Time-lapse

- 2008: Video: Baccalaureate

- 2008: Baccalaureate Photos

- 2008: By the numbers

- 2008: Programs